THE KNOCKOUT is an unusual early Chaplin because he’s only a supporting player, and yet he’s in the Tramp costume (I hesitate to say “playing the Tramp character” because said character is still forming). As successful as Charlie already was, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle was a big star too, in every sense. The director is Mack Sennett per the IMDb, but Wikipedia assigned the job to one Charles Avery, so it’s also an exception in that CC isn’t in charge.

Regrettably missing — the only only lost Chaplin short — is HER FRIEND THE BANDIT, made immediately before this, co-starring and co-directed by Chaplin and Mabel Normand, who evidently had a generous nature and had forgiven Chaplin for refusing to take direction back on the ironically-titled MABEL AT THE WHEEL.

Director Avery impresses at once as an incompetent, with mismatched shots of two hobos atop a freight train and a railyard bull yelling at them, but then Arbuckle enters in a fulsome medium shot, dog under one arm, and it’s quite smartly done. Luke the dog would later appear in Buster Keaton’s screen debut, THE BUTCHER BOY, and was directed by Buster in THE SCARECROW. He was a pro.

The hobos are Hank Mann (prizefighter in CITY LIGHTS), and Grover Ligon (cool science fiction name). It’s not immediately clear why the film spends so much time introducing them.

Some quirky flirtation with Minta Durfee (Roscoe’s real-life wife). Roscoe is getting screen time to develop character and display whimsical interactions which Chaplin had to fight for in his early roles. Then some roughhouse stuff with a local tough: Roscoe does that Three Stooges trick of grabbing the other fellow’s nose then slapping his own hand away. Looks painful for the nose’s owner. Did people ever really do that in street altercations?

When Roscoe turns his back, one of the ruffians starts flirting with Minta: her contemptuous reactions are quite enjoyable. Roscoe returns, and sees red: he advances into an actual close-up, which, owing to its sparse use, has tremendous force. Griffith had been doing this kind of thing in e.g. MUSKETEERS OF PIG ALLEY (1912) and this feels like a parody of the effect.

Violence ensues. Bricks are thrown. With Fatty being so outnumbered, it feels a bit dramatic rather than merely being amusing roughhouse. Minta getting a brick in the face in closeup, no less, is actively unfunny. Seems to me Keystone films don’t always know how to integrate women into the slapstick without it seeming ugly. I mean, it’s already pretty ugly. But Fatty knocking over five men with one brick is pretty amusing.

The gang is led by Al St John and evinces skill and enthusiasm falling into a trough etc. My heart warms nostalgically at the thought of a time when men could earn an honest crust just by falling down flamboyantly and getting up again. Most of these guys had careers into the early thirties at least. Hank Mann would still be turning up as an extra in things like INHERIT THE WIND. James Cagney was blown away by his slapstick skill on THE MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES.

Having shown such pugilistic flair and killer instinct, Fatty is a natural to sign up for the boxing contest where the Act I hobos have just enlisted. St John, his recent rival, certainly thinks this is a swell idea. He no doubt has some cunning revenge in mind.

Fatty’s back to being an underdog, a big innocent kid tricked into the dangerous Dingville Athletic Club. Dingville must be close to Bangville, setting for BANGVILLE POLICE, the first Keystone Kop Komedy. You can tell how they got named.

Meanwhile, hearing that their prospective opponent is a large man, the two volunteer hobos head off to check out the competition. Even as Fatty is being beaten by the punchbag, prey as he is, like Chaplin, to any object that can swing to and fro. Keystone comedians are simply unable to deal with such moving parts, which always strike them (literally) as unpredictable and perhaps demonically possessed.

Fatty persuades the camera to tilt upwards coyly as he removes his overalls, an early version of the hand-over-the-lens gag in Keaton’s ONE WEEK. Then he performs feats of strength that make the hobos flee in terror, even as a real prizefighter shows up (played by Edgar Kennedy with good swagger) and gives them an added shove on their way. But what were the hobos in the film for at all?

Meanwhile, Minta Durfee has disguised herself as a boy. To what end? There was a bit where she seemed to be explaining a costume change to Fatty, but I couldn’t make out why. Just so she can sit in the audience? Or just sheer, exuberant gender-fluidity?

By the way, the IMDb has Chaplin down as the writer of this thing. For decades it was bandied about that Keystone never had scripts, but several of the pesky pamphlets eventually turned up, and it now seems they would generally have a sort of rough scriptment or description of the action made up, which would allow preparation of a few special props, casting, and so on.

PART TWO

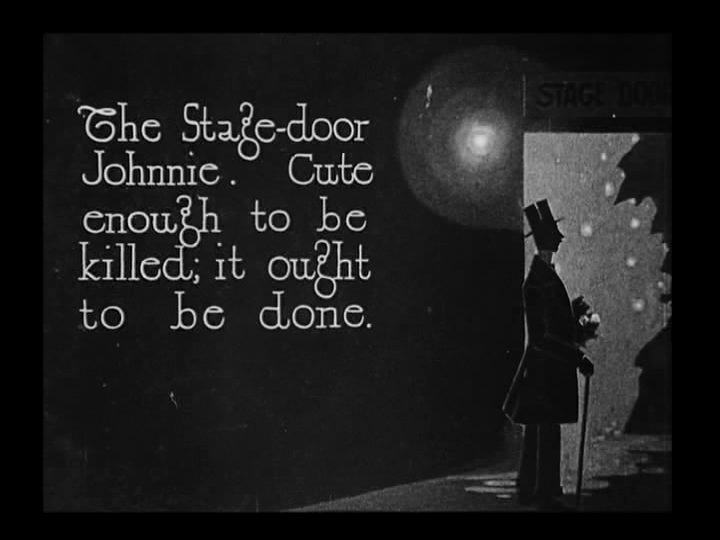

The fight approaches, and so does Chaplin, but Sennett is falling prey to his usual compulsion to cram the frame with funnymen, all fighting for our attention to no particular effect. Enter Mack Swain, with his biggest, droopiest moustache yet. He mutters a few words to the camera, but how even the most observant lipreaders can make anything of this in the shadow of his hanging face-fungus is beyond me. He’s some kind of western desperado and gambler, adding suspense by threatening to shoot Fatty if he loses.

So by the time Charlie prances in, we don’t really need him, but it’s interesting to see him try to hold our attention in this madhouse. He’s wearing the Tramp moustache and suit minus jacket, hat and cane, and he’s not playing drunk. His very energetic entrance suggests he’s been looking at some real-life referees as models for this schtick. So it’s outward bits of Tramp costume and a different character inside, maybe. Still, this may lead to some development of the Tramp…

My hopes seem dashed when he’s immediately punched unconscious. But he’s up again, just as I notice the foreshadowing of CITY LIGHTS’ boxing match. This isn’t AS choreographed, but there are certainly moments where both boxers and ref seem to be moving in sync.

Sennett can’t even give us a decent view of the ring, he insists on broadening the frame to squeeze Swain in, a character who has his own cutaways anyway where he rightly belongs. And the boxers’ teams crowd round the outskirts, dancing about. It’s lively, but it isn’t “a good clean fight” — it’s all distraction, no focus. Chaplin manages some clever moments, dragging himself along by the ropes on his backside, but he’s fighting against a sea of chaotic movement all the time.

His entire performance is delivered in a single camera set-up.

This is a longer than usual “farce comedy” so the ending gets to be bigger than usual, with Fatty stealing Mack’s six shooters and terrorizing everyone. The kops are kalled. The six shooters apparently never need reloading, a handy thing since have you ever tried reloading a pistol in boxing gloves? Come to that, ever tried firing one? You can’t, you know, with your trigger fingers tucked inside.

Charlie disappears from the picture forever (a relatively light day’s work for him, excluding the “writing” which I don’t believe he had any hand in apart from devising his own moves). There’s a long, involved chase with Fatty, Kennedy and the Kops, in which it’s hard to imagine any satisfactory outcome, then Fatty and the Kops fall off a pier into the sea, the end.

What would have made this better?

Having Chaplin appear on the pier, counting Fatty out as he splashes and splutters in the brine.